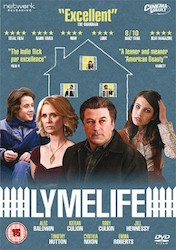

Lymelife

Starring Alec Baldwin, Emma Roberts, Rory Culkin

Directed by Derick Martini

Ever since Jay Gatsby gazed across the bay to an impossibly idealized East Egg, Long Island has represented a fitting encapsulation of the modern American Dream. But unlike Fitzgerald’s classic, Lymelife writers Steven and Derick Martini seek to portray a peculiarly middle-class version of the dream, one that is parceled out into subdivisions and induces malaise that never progresses beyond adolescent angst (for either the teenagers or adults).

A darling of the 2009 Toronto and Sundance Film Festivals, Lymelife chronicles the relationship between two neighboring families in late-70s Long Island. Rory and Kieran Culkin play brothers Scott and Jimmy Bartlett, products of their overprotective mother (Jill Hennessy) and philandering father (Alec Baldwin). Rory especially gives a fresh performance in what could have been a predictable coming-of-age role—that of a sensitive adolescent navigating dystopia at home, bullies at school, and an awakening romantic interest in neighbor Adrianna Bragg (Emma Roberts). For her part, Adrianna is absorbed in newfound sexual maturity, left adrift by a coquettish mother (Cynthia Nixon) and an invalid father (Timothy Hutton), who is ravaged by the late stages of Lyme disease (hence the film’s name).

The relation of the disease to the larger action of the film feels tertiary at best, yet the deep sense of depression and isolation it imprints on its victim, and the recurrent psychotic episodes it produces, create a mirror for the parallel processes of fragmentation and alienation occurring on a widespread scale. It is clear that something about Long Island suburbia has created the condition for this instability. The confined space seems an appropriate setting for the kind of longing that hankers after nothing more than the girl (or spouse) next door, and for the type of social status measured by the size of one’s backyard. To the extent that it captures this sense of constrained and conflicted space, Lymelife does well, particularly in its close-ups and attention to juxtaposition—tightly choreographing a raging father provoking his resisting son, for instance, or slowly panning to a deer on the border of cultivated lawn and wild brush.

Indeed, we sense that the nature of suburban life itself exits between poles. Long Island is wild enough to harbor the deer ticks that carry Lyme disease, yet sufficiently claustrophobic to keep the sufferer huddled in his basement, fixated by the deer he shot on the last day of his healthy life. Suburbia creates enough closeness for neighbors to have been hunting buddies, but not to care for the other during illness, or to prohibit sleeping with the other’s spouse. The unhappy wife and mother mourns the loss of community she had in Queens before moving to a “better life” further out on the island. In short, the Long Island of Lymelife reveals the chasms between health and illness, community and isolation, happiness and despair, and childhood and adulthood. We are left to question whether anyone can emerge authentic from this reality of limbo.

Scott tells Adrianna that he’s “read that one book before…the one where the kid finds out everyone is phony,” clearly referencing The Catcher in the Rye. Well, we’ve seen the story of Lymelife before—be it in literary or cinematographic form—every time we are shown the recurrent cycle of idealism and disillusionment. There is no easy resolution to the conflicts in Lymelife, and no way to gloss its real-life—if somewhat over-dramatized—discord. It shines the brightest in its portrayal of precocious young love, but the shadow of the inhospitable world looms. Just as Adrianna observes that you can hear a train no matter where you are on the island—and, indeed, the plaintive whistle of the Long Island Railroad haunts the film—we are reminded of the ever-present reality of flux, threatening the fragile stability of success, health, family, and maturity.