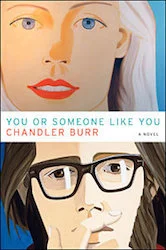

You or Someone Like You

By Chandler Burr

Ecco, 336 pages

$25.99

From Rudyard Kipling’s “We and They”:

All good people agree,

And all good people say,

That all nice people, like Us, are We

And everyone else is They:

But if you cross over the sea,

Instead of just over the way,

You may end by (think of it!) looking on We

As only a sort of They!

At what cost do we humans persist in our habit to cluster together with those who are like “Us”? For Chandler Burr’s accomplished debut novel, You or Someone Like You, this habit relentlessly produces a “They” across the sea, whom we consider to be inferior. Commentaries reverberate across contemporary American culture, especially after the September 11th attacks, pinning this type of exclusivism upon religious fundamentalism—especially of the Islamic and Christian stripe. Similar critiques of Orthodox Judaism, however, remain demure, fearing the accusation, the anathema, of “anti-Semitism.” The particular élan, then, of Chandler Burr’s debut novel consists in its capacity to render vivid—stunningly, achingly vivid—the struggle of the Jewish-American family with a potentially ravaging Jewish Orthodoxy.

The novel starts in New York City, where Howard Rosenbaum falls in love with and marries, against the protests of his Jewish family, the British gentile Anne Hammersmith. When, later, their son Sam is criticized for not being racially pure, Howard defends him, launching into an etymological deconstruction of the word “Jewish,” deftly pointing out that it, like the word “green-ish,” implies admixture. Such narrative cadenzas not only give expression to Burr’s flair as a writer, but also shed insight into the open-ended nature of identity. Sure, Howard’s son is mixed, but so are many of the identity markers we obsessively defend as “pure.” But in spite of Howard’s reasoning, his family’s criticisms of Anne persist; they increasingly close her off—the outsider, the non-Jew. At one family gathering, Howard’s aunt remarks that little Sam is “Beauty itself.” “Yes,” she continues, Anne sitting right beside her. “But the wrong half!”

Howard and Anne move from New York City to Los Angeles to rise in prominence in Hollywood’s film industry. Howard’s career as a film studio executive soars. Anne, quieter, remains in his shadow until she starts a literary salon that quickly becomes popular among Hollywood up-and-ups, catapulting her into minor film industry stardom. In this salon, Anne exercises her hypnotic power to render literature meaningful through personal anecdote. Here she also delivers in-depth disquisitions on culture and language, setting into motion two contrasting forces that hold in tension throughout the novel: a centripetal enclosure into cultural particularism, and a centrifugal push outward toward cultural universalism. The first arises out of Anne’s persisting reverence for high Anglo-American culture, the culture of “Wealth. Power. Social standing. Success. Access. Money talks.” “Speak its language,” she exhorts some Harlem youth. With an irony that perhaps she herself is unaware of, she ventriloquizes her views on the transcendence of cultural specificity through the culturally specific literary canon of Anglo-American “greats”: Shakespeare, Donne, Kipling, Joyce, Auden, among others (David Mamet lying arguably furthest at the edge of this canon). However, pushing outwardly against this is Anne’s own dream, like W.H. Auden’s, of moving beyond any and all forms of cultural enclosure. Auden captured this vision with his life by expatriating from England for America, becoming “a citizen of a polyglot world of transients, misfits, rootless and chaotically blending souls, placing themselves as they wished.” Having herself defected, like Auden, from England, she claims, “I was, I am—nameless.”

Howard and Anne’s effort to push beyond racial and cultural enclosure comes under crisis when their son Sam, a teenager, visits Israel for two weeks. He is there invited to attend an orthodox yeshiva. When administrators discover that his mother is gentile, they violently declare him “trefe,” unclean, and expel him. “Discover the impurity; eliminate the impurity.” This desecration of his own flesh and blood undermines Howard’s ability to keep moving outward, toward a land of “Namelessness.” Distancing himself from Anne, perceiving her more and more the enemy—trefe—he succumbs to the pleas of a rabbi friend: “You are not living fully.” Howard converts, becomes a “Ba’al Teshuva,” a Jew who has committed himself anew to an ancient Orthodox Judaism. Anne “dies” to him as he, possessed, pursues divorce. But even after leaving, he calls Anne and only breathes into the phone, longing for her, but restricted by his rabbi from communicating with the impure. Anne, knowing he loves her, is the only one who can speak: “If you are now a Jew and I am now a Gentile, you have now placed me in a fundamentally different category of human being from yours. We are divided.”

Howard draws himself out of the free flow of identity through a world of open hybridism taking shelter in the enclosures “of those hermetically sealed off.” And this comes at a terrible cost.

Here Burr renders his finest gifts as a novelist. His perfume column for the New York Times Magazine gives venue to his gift for a poetic imagery worthy of the French Symbolists: “Smelling this is like experiencing not banana, nor caramel, nor whipped cream, nor the lightest and most supple tan rich leather driving glove; it is a heated wash through the bloodstream of those concepts wrapped in a very, very blond leaf of the most lightly cured tobacco.” Burr’s past two books on the perfume industry flex his ability to write insightful, entertaining narrative biography. And his writing on sexual orientation and genetics dons the proper garb of science. In You or Someone Like You, Chandler Burr emerges as a master novelist. A Jewish-American himself, he narrates the struggles of this identity in a prose as lithe as it is weighty—ethereal as it is heartbreaking—rendering his characters humanly present and humanely felt. In what is a beautiful debut novel, Burr tunnels into the core of a family romance, there to make us feel the poignancy of its dissolution.

The novel’s brilliance rests equally in its capacity to conceptualize beyond the suffocating enclosures of race and culture and to think a space apart: “Howard and I had escaped from nations,” Anne concludes. “Our own tiny new virtual country is located in a house on a hilltop up a curving drive, the hilltop populated by some lovely palm trees and a well-tended garden, overlooking a large desert valley, high above [Route] 101.” This “country” is as intimate and local as it is borderless and global.

And in the final analysis, what role does Orthodox Judaism play in this wider space of admixture? Or, as another Jewish writer, Tony Kushner, asked in his 1992 play “Angels in America,” “How can a fundamentalist theocratic religion function participatorily in a pluralist secular democracy?” At the end of Kushner’s play, characters of different racial, ideological, and religious backgrounds form a community around Prior, a gay male with AIDS. As the play closes, they all gather around the statue of the Bethesda angel in New York City’s Central Park; surrounding Prior, each character recounts a segment of the biblical story of the Bethesda angel, who healed the sick. They commit now to continuing the angel’s ministry in Prior’s life. This religious story ignites their imaginations, fueling the hard work of healing and loving. That is, Kushner’s play finds a way to re-integrate a softened, non-dogmatic Judaism into contemporary American life. This is a piece of ancient religious lore that is given new life and rendered life giving by its creative re-integration. Or take Jonathan Boyarin’s similar efforts in Thinking in Jewish, where he recounts his return in adulthood to the long-lost Orthodoxy of childhood. He re-infuses it with who he is now as a secularized anthropologist. Stepping into this “transcultural” identity, a “cultural pioneer” across “portable landscapes,” he finds a way to keep the Holy Land alive in himself, and himself in it, by pasting together what he calls a “funky Orthodoxy.”

In Chandler Burr’s universalist vision in You or Someone Like You, Howard and Anne Rosenbaum follow a path away from cultural and racial particularity, toward a land of the “Nameless.” If this is a space in which an ancient Judaism could play a more life-giving role, as it does in Kushner or Boyarin, this reintegration does not emerge as fully, or as magnanimously, as it could have. The power of Chandler Burr’s debut novel is to unleash the potentially disintegrative trauma of racial/religious/cultural exclusivism, then to apply the balm of marital love. The reader will only grow by following Howard and Anne into their “virtual country,” but the reader should not expect to find there the resources for the hard work of reintegration. And this work, I’d contend, remains urgent, for without it we risk spinning backward, centripetally, into the airless enclosures from which the novel has wrested us. An enclosure that produces yet another monstrous “They” across the sea.